Last updated: December 21, 2004

- Home

BOOK

OF PROBLEMS

- Presidential

Workshops and Interactive Discussion Sessions

- at

the

- International

Conferences

- of

the

- Association

for Educational Communications and Technology

- Dallas,

Texas, November 12-16, 2002, and

- Anaheim,

California, October 22-25, 2003

To top of page

INTRODUCTION

In re mathematica ars proponendi

quaestionem pluris facienda est quam solvendi.

The above motto, on the front

page of Georg Cantor's thesis, is cited in Stanislav Ulam's (1991)

autobiography "Adventures of a Mathematician." Cantor's

affirmation that "in mathematics the art of asking questions

is more commonly applied than that of solving problems"

is more than a statement of fact. For someone who, like Cantor,

the creator of Set Theory and discoverer of transfinite numbers,

can look at mathematics as a tremendous accomplishment of the

human mind, the same statement also becomes an article of faith.

To advance in any science, the most important thing is to be

able to ask questions: to ask the right questions and to ask

them the right way. In other words, knowing to formulate what

one does not know is a fundamental step in the advancement of

knowledge.

Despite appearances to the contrary,

we still know very little about human learning. Many respected

educational researchers may not agree with this statement and

claim that, thanks to their work and that of their colleagues,

we have a good handle on the issue of learning, particularly,

that we are pretty well able to create in a deliberate fashion

the conditions necessary for desired learning outcomes. They

are right only to an extent, namely as long as one defines learning

as the consequence of instruction; they are wrong if one is willing

to look at learning as something more broadly defined.

The description below aims at

providing further insight into the problem and makes suggestions

for addressing it through the creation of a Web-based "Book

of Problems." It is the text of a proposal to the Association

for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) to launch

the creation of the Book of Problems initiative at the International

Conference of the AECT to be held in Dallas, Texas, November

12-16, 2002, through a closed workshop for invited researchers,

thinkers and practitioners followed by a public interactive discussion

session. The AECT leadership has accepted the proposal and granted

Presidential Status to both the workshop and the discussion session.

To top of page

ABSTRACT

THE BOOK OF PROBLEMS

(or what we don't know about learning)

Proposal for a Workshop with Interactive

Discussion Session

for the International Conference of the

Association for Educational Communications and Technology

Dallas, TX, November 12-16, 2002

Rationale

The problem addressed in the

proposed workshop cum interactive discussion session is the state

of knowledge about human learning. The underlying rationale is

that we know very little about human learning and that, by clarifying

what we do not know, carefully recording and annotating unsolved

problems, it should be possible to inspire entirely new areas

and new kinds of research into human learning.

The above assertion concerning

the state of knowledge about human learning must be qualified

with reference to how learning is defined. Most people don't

define learning explicitly. However, even if they don't define

it explicitly, it can easily be derived from their writings that

their implicit definitions of learning are limited to what happens

in a purposefully structured learning environment in which desired

attitudinal or competence goals are to be achieved along the

lines of well-designed processes. Such settings are the ones

in which most of the existing research practice is rooted. Basically,

therefore, what we learn from educational research is that "well-designed

instruction works," each specific study adding to our knowledge

of what "well-designed" means and the term "instruction"

referring to processes ranging from highly directive ones that

make people learn in prescribed ways to the more imaginatively

designed environments that allow people to find their own ways

to specifically defined learning goals. There is little research

about learning that takes place beyond the instructional context,

such as incidental learning, or about how attention to the conditions

of learning in multiple settings (instructional as well as non-instructional

ones) may mutually reinforce the depth of our learning. We often

shy away from messy situations.

The past decade has seen an emerging

interest in broadening the way we look at learning to beyond

the instructional context per se. According to De Vaney and Butler

(1996), past definitions of learning have long remained under

the spell of Hilgard's (1948) definition, which states that "learning

is the process by which activity originates or is changed through

training procedures…as distinguished from changes by factors

not attributable to training" (p. 4). Only quite recently,

this close linkage between instruction and learning has started

to disappear. Driscoll (2000), for instance, analyzes the definitional

assumptions shared by current learning theories. She notes that,

in order "to be considered learning, a change in performance

or performance potential must come about as a result of the learner's

experience and interaction with the world" (p. 11;

emphasis added). Tessmer and Richey (1997) argue for broadening

the instructional design concerns to beyond the instructional

context as such and to recognize "context" as an important

factor in the design of instruction. Shotter (e.g. 1997) emphasizes

the dialogic nature of learning, as do Savery and Duffy (1995)

with particular reference to constructivist learning environments.

John-Steiner (2000) elevates the idea of dialogue to the level

of creative collaboration. Building on these different definitional

developments, J. Visser (2001) proposes, while attempting to

bring the various pieces together, a definition that looks at

learning as a disposition to dialogue rather than as the collection

of mental processes that result from such a disposition. Visser's

definition furthermore recognizes the ecological integration

of diverse levels of organizational complexity at which the dialogue

takes place, involving, in addition to individuals, social entities

of varying dimension. It also sees as the ultimate purpose of

the dialogue the ability to interact constructively with change,

rather than the mere acquisition of particular behaviors necessary

for such interaction. Recently, Educational Technology magazine

dedicated an entire special issue (Y. L. Visser, Rowland &

J. Visser, 2002) to the issue of broadening the definition of

learning and the implications this would have for educators and

educational technologists.

Looking at human learning from

the perspective of the above mentioned emerging shift in definitional

assumptions provides a clear sense of the growing awareness of

how much more complex the world of learning is than we ever thought.

Consequently, it also heightens our consciousness of how little

we actually know about that complex phenomenon. Confronted by

this enhanced awareness of the limitations of our knowledge,

it is worth looking at the history of science and ask ourselves

if anything can be learned from what we know about the ways in

which human knowledge developed, going from crisis to crisis.

Progress in several fields of

intellectual endeavor has greatly benefited from open dialogue

among scientists who were concerned with what they did not know,

rather than with what they already knew. A clear example can

be found in the history of how our understanding of the fundamental

structure of matter and energy advanced throughout the twentieth

century, particularly during the first half of it, thanks to

the willingness and audacity of the scientists involved to keep

challenging each other at the frontier of what was known, i.e.

looking out over the vast unknown (e.g. Pais, 1991).

Another interesting example,

which inspires the current proposal, can be drawn from the history

of mathematics in the first half of the 20th century. The Polish

school of mathematicians, who used to gather in the cafés

and tearooms in such places as Lwów, developed a book

in which they inscribed - and annotated - the great unsolved

problems of their discipline. The book was kept in the Scottish

Café in Lwów (whence its name: The Scottish Book)

and handed by a waiter to the mathematicians in attendance when

they so wanted. Miraculously, this fascinating notebook, the

collaborative conscience of the mathematicians of the time regarding

what they did not know, escaped the devastation of World War

II and its aftermath and eventually got published. While it was

kept, it used to help challenge those who wanted to be challenged

to try and solve these problems. (The story of the Scottish Book

can be found in Ulam [1991]. The print edition of the Book is

hard to come by. A version of it, which was edited and translated

by Ulam, was published in 1957 in Los Alamos, NM, by the Los

Alamos Scientific Laboratory. An excerpt of the Book can be found

at http://www.icm.edu.pl/home/delta/delta2/dlt0209.html.)

It is contended that in the sciences

of learning we have reached a breakthrough stage that calls for

a similar honest reflection among scientists on what they do

not know as a means to move forward. Consequently, it is appropriate

for those scientists who have an interest in broadening and deepening

the meaning of learning to do what the earlier referred Polish

mathematicians did: keep a book of what they don't yet know -

not the nitty-gritty of it, but the really important problems

- and use it as a source of inspiration for them and others to

advance. While it would be attractive to use coffee and tea houses

as gathering places for the discussion of such matters, it is

now more appropriate to make this a Web-enabled effort as far

as recording and annotating of the problems is concerned. The

actual gatherings that contribute to filling the book progressively

may well be linked to events such as the annual meetings of AECT

and other professional organizations where scientists pertaining

to the multiple disciplines relating to the transdisciplinary

fied of the sciences of learning come together anyway in a more

or less frequent fashion. Such gatherings can be complemented

by various modes of electronic interaction in between of face-to-face

events. The current proposal thus aims at starting the effort

off on the occasion of the International Conference of the AECT

in November 2002 in Dallas, Texas.

Nature of the proposed activity

The proposed activity will bring

together selectively invited prominent researchers and thinkers

to discuss ways of broadening research agendas in the area of

research on human learning. It is proposed that the group of

invitees first meet in a workshop-style conducted private

session in the framework of the AECT International Conference.

This proposed private workshop-type session will be followed

by a two-hour session open to the conference attendees

consisting of two parts: (1) presentation by the invitees of

the results of their private meeting and (2) a discussion, involving

invitees and attendees together, of the problems under consideration.

This latter interactive session will particularly aim at critically

appraising the work of the invitees and providing an opportunity

for others to start contributing to the process envisioned by

the Book of Problems. There will be no paper presentations in

the traditional sense of the word. Rather, in the running up

to the session, a concept paper will be prepared by the chair

and circulated among the group of invited scientists with the

aim of enhancing the document. While the process will start off

with a particular number of invited scientists, it is expected

and will be encouraged that the initial group will identify others

who should be expected to make useful contributions to the Book

of Problems. The enhanced version of the concept paper, which

will increasingly reflect the views of a growing number of scientists,

will guide the discussions during both the private session and

the interactive discussion session. In addition to being made

available to the invitees and attendees of the proposed sessions,

the concept paper will also be available via the World Wide Web.

Purpose of the session

The workshop cum interactive

discussion session, both through the process of its preparation

and implementation, has the following objectives:

- To create awareness among the

AECT membership at large of the importance of broadening and

deepening the meaning of learning.

- To raise the level of sensitivity

and heighten interest among the research community to explore

new fields and modalities of research into human learning.

- To make a start with the above

referred Web-enabled "Book of Problems" as a means

to consolidate and further develop the above research interests.

- To make a start with establishing

a research community interested in collaborating, where appropriate

in a transdisciplinary mode, on key problems in the development

of the sciences of learning.

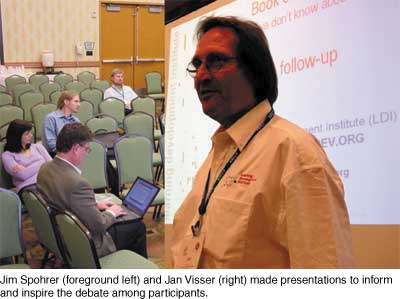

Panelists

Chair/organizer of the activity

is Jan Visser, President, Learning Development Institute

(LDI) and Principal Investigator of LDI's Meaning of Learning

(MOL) project. For the purpose of organizing the session and

its follow-up, he will be assisted by Yusra Laila Visser,

Researcher at Florida State University and co-investigator of

LDI's MOL project and David L. Solomon, Research Fellow

with LDI as well as Vice President, Creative Director at BBDO

Detroit. They will also themselves contribute to the process

envisioned by the Book of Problems.

The following scholars, listed

alphabetically, have at an earlier stage, independently of the

idea to start this off at the 2002 AECT International Conference,

been appoached and expressed interest in and commitment to being

part of the effort to write the Book of Problems:

Carl Bereiter (University of Toronto)

Ron Burnett (Emily Carr Institute of Art + Design)

Marcy Driscoll (Florida State University)

Vera John-Steiner (University of New Mexico)

David Jonassen (University of Missouri)

Basarab Nicolescu (International Center for Transdisciplinary

Studies and Research & Université Paris VI)

David Perkins (Harvard University)

Rita Richey (Wayne State University)

Gavriel Salomon (University of Haifa)

Marlene Scardamalia (University of Toronto)

Other researchers will be contacted

after AECT will have agreed to run the activity in the framework

of the 2002 International Conference in Dallas and will have

granted Presidential status to it.

Procedures for the interactive discussion

session

While procedures for the private

workshop session, including the determination of how much time

should be allocated to it, will be worked out in consultation

with the prospective participants, it seems fair at this stage

to describe how the interactive discussion session, which involves

the participation of regular conference attendees, is foreseen

to be conducted.

As mentioned, there will be no

paper presentations during the proposed session. An expectedly

large proportion of the participants will come well prepared

for the debate. They include researchers alerted to the opportunity

by the organizers and the team of invited scientists who have

already joined the initiative. In addition, other interested

researchers will themselves take the initiative to contact the

organizers on the basis of information available in the program

and on the Web pages of the AECT 2002 International Conference

or on the Web site of the Learning Development Institute. Participants

who "discover" the session only while in Dallas will

be somewhat less prepared, but everything possible will be done

to make their participation as effective as possible for the

stated purposes of the session and as beneficial as possible

for themselves. This may require a very brief summary of issues

at the outset of the interactive session.

The value of the session lies

in the energetic participation of all its participants in the

debate. The chair will apply his considerable experience in conducting

such sessions in ways that create maximum involvement of the

participants. Depending on the size of the audience, part of

the debate during the proposed two-hour session may be conducted

in small groups so as to raise the level of creative engagement.

In line with the set purpose for panel discussions, emphasis

will be on the ad hoc interchange, recognizing the value of both

divergence and convergence of positions in clarifying the issues

concerned. To allow this ad hoc interchange to develop effectively,

a fair level of improvisation will characterize the procedures

of this session.

Long-term issue

It is expected that the community

of scientists, whose initial establishment is aimed at through

the proposed activity, while begun in the AECT context, will

grow beyond that same context. The sciences of learning constitute

a truly transdisciplinary field. The Learning Development Institute

(http://www.learndev.org) and its partner, the International

Center for Transdisciplinary Studies and Research (CIRET; http://perso.club-internet.fr/nicol/ciret/)

will work together to achieve that aim. In doing so, opportunities

will be sought to involve scientists active in different fields

pertaining to the sciences of learning by proposing follow-up

sessions to different other organized bodies of scientists, such

as those active in the areas of mass communication, neuroscience,

linguistics, and the development of scientific competence.

References

De Vaney, A. & Butler, R.

P. (1996). Voices of the founders: Early discourses in educational

technology. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research

for educational communications and technology. New York,

NY: Simon and Schuster Macmillan (p. 3-45).

Driscoll, M. P. (2000). Psychology

of learning for instruction. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &

Bacon.

Hilgard, E. R. (1948). Unconscious

processes and man's rationality. Urbana, IL (as quoted in

De Vaney & Butler, 1996).

John-Steiner, V. (2000). Creative

collaboration. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Pais, A. (1991). Niels Bohr's

times: in physics, philosophy, and polity. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press.

Savery, J. R., and Duffy, T.

M. (1995). Problem based learning: An instructional model and

its constructivist framework. Educational Technology, 35(5),

31-38.

Shotter, J. (1997). The social

construction of our 'inner' lives. Journal of Constructivist

Psychology, 10, 7-24.

Tessmer, M. & Richey, R.

C. (1997). The role of context in learning and instructional

design. Educational Technology Research and Development 45(2),

85-115.

Ulam, S. M. (1991). Adventures

of a mathematician. Berkeley, CA: University of California

Press.

Visser, J. (2001). Integrity,

completeness and comprehensiveness of the learning environment:

Meeting the basic learning needs of all throughout life. In D.

N. Aspin, J. D. Chapman, M. J. Hatton and Y. Sawano (Eds), International

Handbook of Lifelong Learning. Dordrecht, The Netherlands:

Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Visser, Y. L., Rowland, G, &

Visser, J. (Eds.) (2002). Special issue on broadening the definition

of learning. Educational Technology, 42(2) - entire issue.

To top of page

THE "BOOK OF

PROBLEMS" COMMUNITY OF SCHOLARS

Overview of members of the

Book of Problems (BOP) community of scholars alphabetically listed

by last name as of September 24, 2002. Members whose names are preceded by a red bar will

be present in Dallas; those whose names are preceded by a green

bar will interact with the participants of the Dallas workshop

by teleconferencing. All other members, whose names are preceded

by a yellow bar, contribute to the initiative in writing and

possibly through alternative mechanisms of scientific exchange

that may, in time, be decided upon. As the initiative progresses,

the above list is expected to grow as more individuals are being

approached.The column with biographical notes is continually

under construction.

New names are being added as the community grows.

Those whose names are preceded by a blue bar joined the community

on the occasion of the Anaheim, CA, workshop and Special Panel

Session (see below) at AECT 2003.

|

|

Name |

Affiliation |

Biographical notes |

|

|

- John Bransford

|

Vanderbilt University |

John D. Bransford is Centennial Professor of

Psychology and Education and Co-Director of the Learning Technology

Center at Vanderbilt University. He is an internationally renowned

scholar in the areas of cognition and technology. His collaborative

involvement over several decades in research on human learning,

memory and problem solving has helped shape the "cognitive

revolution" in psychology. While developing the Learning

Technology Center at Vanderbilt, John, who is an award winning

author and developer, and his colleagues have contributed decisively

to the thoughtful use of technology for the development and improvement

of school-based learning through such programs as the Jasper

Woodbury Problem Solving Series in Mathematics, The Scientists

in Action Series, and the Little Planet Literacy Series, which

are being used around the world. Closer to home they are involved,

among other efforts, in a "Great Beginnings" project

in Nashville that links homes, schools and members of the broader

community through innovative uses of technology. John plays a

prominent role in synthesizing findings from multiple areas of

research to create a "user friendly" theory of human

learning. |

|

|

- Ron Burnett

|

Emily Carr Institute of Art + Design |

Ron Burnett is a Canadian communications scholar

and social/cultural critic. He has a particular interest in popular

culture, hypermedia, and postmodern media communities. He is

the author of Cultures of Vision: Images, Media and the Imaginary,

and the forthcoming How images think, as well as founder

and editor of Ciné-Tracts Magazine (1976-1983).

He is President of the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design

in Vancouver, BC, Canada. Prior to that he was Director and Associate

Professor of Communications and Cultural Studies in the Graduate

Program in Communications at McGill University in Montreal, Québec,

Canada. |

|

|

- David Cavallo

|

MIT Media Lab |

David Cavallo is Principal Investigator of the

Future of Learning Group at the Media Lab of the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology. David's work is particularly motivated

by the concern that the latent learning potential of the world

population has been grossly underestimated as a result of prevailing

mindsets that limit the design of interventions to improve the

evolution of the global learning environment. |

|

|

- Marcy Driscoll

|

Florida State University |

Marcy Driscoll is Program Leader and Professor

of Instructional Systems and Learning Psychology in the Instructional

Systems Program of the Department of Educational Research at

Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida. She is the author

of multiple textbooks, among which the award winning Psychology

of learning for instruction and, together with Robert Gagné,

Essentials of learning for instruction, as well as numerous

other publications. Marcy has a wide array of editorial responsibilities.

She held and holds important leadership positions in the professional

communities pertaining to her areas of interest and research. |

|

|

- Alison Gopnik

|

University of California at Berkeley |

Alison Gopnik is a professor of psychology at

the University of California at Berkeley. Her research focuses

on early human development. She is specifically interested in

questions regarding how children come to understand the world

around them and what their "theories of mind" are,

particularly in terms of children's early understanding of visual

perception and desire as well as their understanding of causality

and their explanations of events. She is also interested in the

interactions between children's language and their cognitive

development. Alison is widely known for such books as Words,

Thoughts, and Theories, which she wrote with Andrew Meltzoff,

and The Scientist in the Crib: Minds, Brains, and How Children

Learn, which she coauthored with Patricia Kuhl and Andrew

Meltzoff. The investigations reflected on in these books are

informed by "the theory theory", the idea that children

understand the world by using strategies that are similar to

and perhaps even identical with processes of theory change in

science. |

|

|

- Susan Greenfield

|

University of Oxford |

Baroness Susan A Greenfield, CBE, is a neuroscientist

whose multidisciplinary research focuses on neuronal mechanisms

in the brain that are common to regions affected in both Alzheimer's

and Parkinson's disease. She is particularly interested in strategies

to arrest neuronal death in these disorders. A Professor of Pharmacology

at Oxford University and Professor of Physics at Gresham College,

as well as Fellow of Lincoln College, Susan is widely known,

both in the UK and beyond, for her public lecturing, including

via the BBC. She is the first female director of the Royal Institution,

established in 1799 to "diffuse science for common purposes

of life." Among her many publications are the best-selling

The human brain: A guided tour as well as Journey to

the centers of the mind: Toward a science of consciousness

and The private life of the brain: Emotions, consciousness

and the secret of the self. |

|

|

- Vera John-Steiner

|

University of New Mexico |

Vera John-Steiner is a social and developmental

psychologist with a particular interest in the role of language

in learning, collaborative cognition and complex collaboration.

She wrote, among other books Notebooks of the mind, which

won several awards, and Creative collaboration. Vera is

Presidential Professor in Linguistics & Educational Psychology,

& Language, Literacy, & Sociocultural Studies at the

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. |

|

|

- David Jonassen

|

University of Missouri |

David Jonassen has taught and pursued his research

goals around the world at different universities in the USA as

well as in the Netherlands, France, Norway, Australia, Austria,

Germany, Malaysia, Poland, Scotland, Singapore, Taiwan, and soon

Korea. His background is in educational media and experimental

educational psychology. David, who is considered among the top

scholars in the world in the field of instructional design and

technology, is the author or coordinating editor of a great many

books and has written numerous articles, chapters, and reports

on text design, task analysis, instructional design, computer-based

learning, hypermedia, individual differences and learning, and

technology in learning. His current research focuses on cognitive

tools for learning, knowledge representation, computer-supported

collaborative argumentation, cognitive task analysis, and especially

problem solving. He has received numerous honors for excellence

in both research and writing. |

|

|

- Steve Lansing

|

University of Arizona |

J. Stephen Lansing is an ecological anthropologist,

well known for his research on the emergence of cooperation within

and among groups of humans who collaboratively interact with

the same key environmental conditions, such as the rice farmers

in Balinese watersheds. Within the context of the above research

interest, Steve has been actively and successfully involved in

the development of adaptive agent simulation models that can

predict the emergence of cooperation at multiple hierarchical

levels as a function of human-environmental interactions. He

is the author of a variety of books. Priests and Programmers:

Technologies of Power in the Engineered Landscape of Bali

is probably the best known among those books. |

|

|

- Leon Lederman

|

Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy |

Leon M. Lederman is an experimental physicist

who received the 1988 Nobel Prize for his part in developing

the neutrino beam method and the demonstration of the doublet

structure of the leptons through the discovery of the muon neutrino.

Since retiring from his function as Director of the Fermi National

Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois, he has dedicated

his efforts to helping others to discover the beauty of the world

through science. Thus he helped organize a Teachers' Academy

for Mathematics and Science, designed to retrain 20 000 primary

school teachers in the Chicago Public Schools in the art of teaching

science and mathematics. In addition, he has been involved with

science education for gifted children and with public understanding

of science. He helped to found the Illinois Mathematics and Science

Academy, a three year residential public school for gifted children

in the State of Illinois. He also founded ARISE, a program to

modernize the teaching of science in high schools. |

|

|

- Federico Mayor

|

Culture of Peace Foundation & Universidad

Autónoma de Madrid |

Federico Mayor Zaragosa is a biochemist of renown,

whose publications focus, among other areas, on the metabolism

of the brain and the biochemical processes and pathology of the

newly born. He founded and directed the Centro de Biología

Molecular Severo Ochoa at the Universidad Autónoma de

Madrid. Federico is also a poet, a thinker and one of the great

humanists of our time. He served as Director-General of UNESCO

from 1987 to 1999. Much of his attention during that period was

directed at leading the Organization back to its original roots,

namely its role in fomenting a culture of peace, promoting tolerance

and understanding among the peoples. As part of this objective

he took great care to advance human learning in its rich variety

of appearances among all members of planetary society.

Following an effective two mandates at the helm of UNESCO, he

subsequently founded and presides over the Fundación Cultura

de Paz, headquartered in Madrid, Spain. |

|

|

- Basarab Nicolescu

|

Centre International de Recherches et d'Études

Transdisciplinaires & Université de Paris VI |

Basarab Nicolescu is a widely published theoretical

physicist who works with the Centre National de la Recherche

Scientifique at the University of Paris VI, France. He is also

Founding President of the International Centre for Transdisciplinary

Research and Studies in Paris and Member of the Romanian Academy.

He is winner of the Silver Medal of the French Academy for one

of his many books and of the Benjamin Franklin Award for Best

History Book for another book. His authoring activities range

from poetry, via philosophy, ethics, consciousness and spirituality,

to such down-to-earth things as Hadron scattering or the Odderon

intercept in perturbative QCD. |

|

|

- Seymour Papert

|

MIT Media Lab |

Seymour Papert is a South Africa born mathemetician

and an early artificial intelligence pioneer with a history of

active participation in the movement to abolish apartheid in

his native country. He engaged in mathematical research during

the 1950s at the University of Cambridge before joining Jean

Piaget at the University of Geneva with whom he worked for five

years until 1963. The latter collaboration prompted his interest

in using mathematics as a way to understand how children learn

and think. Seymour is probably best known around the world -

through projects he carried out in all continents and via his

work, which has been widely translated - for his pioneering ideas

about children's use of computers as a means to foster learning,

thinking and creativity. Among his best known works are Mindstorms:

Children, computers and powerful ideas (1980) and The

children's machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer

(1992). In the early 1960's he founded, together with Marvin

Minsky, the Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT. He is also a

founding faculty member of the MIT Media Lab and inventor of

the Logo programming language, putting children in control of

computater technology. Living in Maine, he spends part of his

time working in the Maine Youth Center in Portland, the state's

facility for teenagers convicted of serious offenses. |

|

|

- David Perkins

|

Harvard University |

David Perkins originates from the fields of mathematics

and artificial intelligence, in which he obtained his Ph.D. at

MIT. He is a founding member of the well-known Project Zero at

the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a project which he

co-directed for more than 25 years. Project Zero initially focused

on the psychology and philosophy of education in the arts, but

later broadened its perspective to encompass cognitive development

and cognitive skills in both humanistic and scientific domains.

Singling out any of the multiple books David has written would

probably do a disservice to seeing the broadness of his interest

in the human mind. |

|

|

- Nick Rawlins

|

University of Oxford |

Nicholas Rawlins is a psychologist at the Experimental

Psychology Department of the University of Oxford, UK, where

he is a Fellow of University College and Professor of Behavioral

Neuroscience. His research focuses on animal learning and memory,

brain mechanisms of memory storage, animal models of psychosis,

attentional deficits in schizophrenia, and FMRI studies of pain

in humans. |

|

|

- Rita Richey

|

Wayne State University |

Rita C. Richey is Professor and Program Coordinator

in Instructional Technology for the College of Education at Wayne

State University. She has a background in English, psychology

and instructional technology and has won many awards, both for

her outstanding performance as a teacher at Wayne State, such

as the 1997 Outstanding Graduate Mentor Award and the 1985 President's

Award for Excellence in Teaching, and for the quality of the

books she produces, including the 1995 Outstanding Book in Instructional

Development award of the Association for Educational Communications

and Technology. Rita's research focuses on Instructional Design

Effectiveness and Instructional Design Processes; Transfer of

Training and Organizational Performance Improvement; and Competency

Modelling. |

|

|

- Gavriel Salomon

|

University of Haifa |

Gavriel Salomon is professor of educational psychology

and past dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of

Haifa, Israel, where he is also co-director of the Center for

Research on Peace Education. Gabi is well known for his work

on a broad range of topics at the interface of educational psychology

and communication, including the cognitive effects of media's

symbol systems; the expenditure of mental effort; mindfulness

and mindlessness; organizational change; the design of intelligent

computer tools; the design and systemic study of technology-afforded

learning environments; and - more recently - research on peace

education. He has an extensive publication record in all of the

above areas, his most recent book being Peace education: The

concept, principles, and practices around the world. Gabi

is the recipient of various awards, including the Israel National

Award for life long achievements in educational research (2001). |

|

|

- David Scott

|

University of Massachusetts at Amherst |

David K. Scott owes his motivation to having

been born and grown up on the northernmost of the Orkney Islands

in Scotland. The setting exposed him at an early age to the forces

of nature which led to his interest in physics. The commitment

of his family and community to helping him attend boarding school

from the age of ten and to further pursue his academic interests

has been a shaping force in his concern for the "democractization

of privilege." David has a distinguished career both as

a nuclear scientist and as an administrator, having served most

recently as Chancellor of the Amherst campus of the University

of Massachusetts from 1993 to 2001. He advocates and has developed

policies for an integrative university in which transdisciplinary

research and holistic learning communities overcome the fragmentation

of knowledge and incite the development of wise human beings

motivated to create a better world. |

|

|

- Jan Servaes

|

Katholieke Universiteit Brussel |

Jan Servaes is Dean of the Faculty of Social

and Political Sciences as well as Professor and Chair of the

Department of Communication at the Katholieke Universiteit Brussel

in Belgium. He is director of the Research and Documentation

Centre 'Communication for Social Change' (CSC), and Coordinator

of the European Consortium for Communications Research (ECCR).

In addition to Belgium (Antwerp and Brussels), he has taught

International Communication and Development Communication in

the USA (Cornell), The Netherlands (Nijmegen), and Thailand (Thammasat,

Bangkok). He is also President of the International Association

of Media and Communication Research (IAMCR), in charge of academic

publications and research. He has undertaken research, development,

and advisory work around the world and is widely known as the

author of journal articles and books on such topics as international

and development communication; media policies; social change;

and human rights and conflict management. |

|

|

- John Shotter

|

University of New Hampshire |

John Shotter is a professor of interpersonal

relations in the Department of Communication, University of New

Hampshire. Author of such early (1975) works as Images of

Man in Psychological Research and more recent (1993) ones

such as Cultural Politics of Everyday Life: Social Constructionism,

Rhetoric, and Knowing of the Third Kind and Conversational

Realities: the Construction of Life through Language, he

has a long standing interest in the social conditions conducive

to people having a voice in the development of participatory

democracies and civil societies. In recent times, John has begun

to look beyond current versions of Social Constructionism, toward

the surrounding circumstances that make such a movement possible.

In this context, the move first to a focus on joint action, then

to dialogically-structured or 'chiasmically organized' (Merleau-Ponty,

1968) activities, is a central part of his interest in participatory

modes of life and inquiry. |

|

|

- David Solomon

|

- BBDO Detroit &

- Learning Development Institute

|

David L. Solomon is Vice President, Creative

Director in Training Operations at BBDO Detroit, the agency of

record for DaimlerChrysler Corporation. He has more than 14 years

experience designing, developing and implementing learning and

performance improvement solutions for multinational and privately

held businesses. David has held faculty/adjunct faculty positions

in the Instructional Technology program at Wayne State University;

the Human Resource Development department at Oakland University;

and the communications department at Walsh College. David's research

has explored the various ways in which philosophy shapes instructional

design practice, including an investigation of perspectives,

foundations, and elements of post-modernism in theory and practice.

He joined the Learning Development Institute in 2000 as a Research

Fellow on the Meaning of Learning (MOL) project. |

|

|

- Michael Spector

|

Syracuse University |

Michael Spector is a philosopher by original

background and is currently Professor and Chair, Instructional

Design, Development and Evaluation at Syracuse University, Syracuse,

New York, USA. He is also a visiting Professor of Information

Science at the University of Bergen, Norway and a member of the

International Board of Standards for Training, Performance and

Instruction. In addition, he is active in the context of numerous

professional organizations in the area of education, computing

and artificial intelligence. Mike's research and development

interests cover such fields as intelligent performance support

for instructional design; acquisition of complex cognitive skills;

and the design of system dynamics based learning environments.

He also teaches graduate seminars on topics related to the planning

and implementation of learning environments and instructional

computing systems. |

|

|

- James C. Spohrer

|

IBM Almaden Research Center |

Jim Spohrer is a senior manager at IBM's Almaden

Research Center in San Jose, California. He is also a core team

member of the Educational Object Economy (EOE) foundation, which

he helped start while a Distinguished Scientist in Apple's Learning

Communities Group. At IBM Jim focuses on next generation user

experience. In the EOE context his long-term goal is to create

virtual learning community that goes critical as it grows in

members and member generated open source assets, operating under

an intellectual capital appreciation license (like a software

bank,. borrow code, and repay in interest that is code enhancements

or other useful meta-content). Jim's research interests revolve

around understanding learning platforms and learning communities.

He is especially interested in pedagogy, production and proliferation

aspects of engaging, effective, and economically viable learning

environments. Jim received his Computer Science Ph.D.from Yale

in 1989 and his Physics B.S. from MIT in 1978. In 1989, Jim was

a Visiting Scholar at the University of Rome La Sapienza in Italy. |

|

|

- John Stein

|

University of Oxford |

John Stein is a physiologist at the University

Laboratory of Physiology of the University of Oxford, UK, where

he is a Fellow of Magdalen College and Professor of Physiology.

His research focuses on auditory and visual perceptual impairments

suffered by dyslexic children as well as on the role of the posterior

parietal cortex, basal ganglia and cerebellum in the control

of movement. As an outgrowth of his interest in the physiology

of learning to read and dyslexia, John is setting up a study

of the strengths of dyslexics that may predispose them to be

artists,elite IT and other entrepreneurs. He is also involved

in an attempt to design tests of deep learning styles for detecting

unusual talent in the inadequately taught. |

|

|

- Robert Sternberg

|

Yale University |

Robert Sternberg owes his childhood interest

in psychology to his very poor performance on IQ tests. He credits

his extraordinary academic and professional career in later years

to the exceptional role of mentors in his life. Bob is now the

IBM Professor of Psychology and Education at the Department of

Psychology, Yale University. He is well-known for his work in

the fields of intelligence, wisdom, and creativity, and has published

some 900 books and articles in these fields. He graduated Summa

Cum Laude Phi Beta Kappa from Yale and subsequently received

his Ph.D. from Stanford. He is a fellow of the American Academy

of Arts and Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement

of Science, the American Psychological Association (of which

he is currently President-Elect and will become President on

January 1, 2003), and the American Psychological Society. He

has won four awards from the American Educational Research Association,

as well as numerous awards from other organizations. Bob's research

focuses on higher mental functions; thinking styles; cognitive

modifiability; leadership; and love and hate. |

|

|

- Jan Visser

|

Learning Development Institute |

Jan Visser is a theoretical physicist, turned

educator, turned documentary filmmaker, turned instructional

designer and researcher of human learning. He has a profound

interest in the arts and is a practicing musician. As a physicist

he dedicated himself to exploring the quantum mechanical aspects

of molecular biological structures; as a documentary filmmaker

his interest was drawn to the role of imagination in children's

(and adults') coming to grips with the seemingly unalterable

facts of life; as a science educator he explored developing the

scientific mind through the understanding of the historical and

epistemological development of science as well as the experiential

involvement with natural phenomena; as an instructional designer

he dedicated himself to the exploration and management within

the learning environment of affective conditions, whereas as

a learning scientist his attention goes to human learning as

a complex adaptive phenomenon. Jan is president of the Learning

Development Institute and former UNESCO Director for Learning

Without Frontiers. He has lived and worked around the world,

including a residence of some 20 years in Africa. |

|

|

- Muriel Visser

|

Learning Development Institute & Florida

State University |

Muriel Visser has an academic background in rural

sociology (Wageningen University, Netherlands), distance education

(University of London and Educational Extension College, Cambridge,

UK), and mass communication (Florida State University). Her professional

experience has focused on the design and management of international

development projects, particularly in Africa. Muriel's current

research interests focus on human learning and behavioral change

as it relates to living with and in the presence of HIV and AIDS.

In the context of her research she is also asking herself questions

regarding research methodological issues (particularly how we

best get to know what we want to know in non-traditional research

settings). |

|

|

- Yusra Laila Visser

|

Learning Development Institute & Florida

State University |

Yusra Visser spent the first 18 years of her

life in southeast Africa, learning much from growing up amidst

the wonders and the difficulties of postcolonial states, witnessing

both the splendor of the diversity of lifestyles and cultures

in those regions and the ravaging effects of war, poverty, and

disease. While as a teenager at the Waterford-Kamhlaba United

World College in Mbabane, Swaziland, she learned about the values

of a solid education as well as the importance of political action

and consciousness, about social service, and about the use of

systematic inquiry for interpreting the attributes of the surrounding

world. Those early experiences set the stage for some of her

later choices, such as her specialization in Africa Studies and

Political Economy while doing her undergraduate work at American

University in Washington, DC, and her later focus on problem

based learning for her graduate work at Florida State University.

Yusra in Principal Investigator for the development of the Problem-Oriented

Learning focus area at the Learning Development Institute as

well as a researcher active in LDI's the Meaning of Learning

(MOL) and The Scientific Mind (TSM) focus areas. |

-

- To top of page

INPUTS INTO A COLLABORATIVE

DIALOGUE

In preparation of the Dallas

workshop mentioned above, members of the BOP community have been

requested to elucidate what, from their point of view, are the

important questions to be addressed regarding what we do not

know about learning. Following are the responses of the various

contributors posted in the order in which final versions were

received and preceded by a linked alphabetically organized list

of the authors and titles.

-

- Back to list of contributors

Joint action, and

the chiasmic inter-relating of spontaneously responsive, bodily

activities

John Shotter

Department of Communication

University of New Hampshire

Durham, NH 03824-3586

Let me begin with a quotation

from Vygotsky (1986): "The general law of development says

that awareness and deliberate control appear only during a very

advanced stage in the development of a mental function, after

it has been used and practiced unconsciously and spontaneously.

In order to subject a function to intellectual and volitional

control, we must first possess it" (p. 168).

As I see it, the main unsolved

problem in learning and teaching is the spontaneous, expressive

responsiveness of our bodies to events that matter to

us in our surroundings - to those events that, as Bateson (1972)

so famously put it, are a difference "that makes a difference

[to us]" (p.286).

I want to emphasize the importance

of our spontanous, bodily responsiveness, because I want to draw

attention to how the chiasmic (i) or dialogical-intertwining of

influences from two or more distinct sources of embodied living

activity makes possible a special kind of first-time creativity,

the creation of new forms of living activity, not possible in

any other way. Only in this way is it possible to develop a way

of acting in response to, or in relation to, the unique character

of our current surroundings, to develop a practical way of "going

on," in Wittgenstein's (1953) terms, in relation to the

concrete world around us (Shotter, in press).

In referring to a "first-time"

creativity, I have in mind a phrase of Garfinkel's (1967). In

his discussion of a community's shared "accounting practices

(ii),"

he remarks that by their use, a member of a community "makes

familiar, commonplace activities of everyday life recognizable

as familiar," and that, on each new occasion, it is done

for yet "'another first time'" (p. 9). This is because,

as well as being known to us as the objects they are,

we also require a shaped and vectored sense of their presence

(see Shotter, in press again), i.e., how in their otherness they

act as agencies in our lives inviting us to act toward

them in some ways while discouraging us from acting toward

them in others. Not only is this apparent to us in our physical

movements - that those around us have a valency for us

in that we must avoid them - but especially in our utterances.

Indeed, as Bakhtin (1986) puts it: "...the word is expressive,

but... this expression does not inhere in the word itself.

It originates at the point of contact between the word and actual

reality, under the conditions of that real situation articulated

by the individual utterance. In this case the word appears as

an expression of some evaluative position of an individual

person..." (p.88, my emphasis).

This means that when someone

acts, their activity cannot be accounted as wholly their own

activity - for a person's acts are always partly 'shaped' by

the acts of the others around them - and this is where all the

strangeness of the dialogical begins (see Shotter, 1980, 1984,

1993a, 1993b). This kind of continuously occurring, first-time,

unpredictable, and unanticipated but nonetheless (once it has

occurred) intelligibly evaluative creativity, has not yet, I

want to claim, been adequately appreciated and characterized

in our social thought.

Indeed, the pervasive Cartesianism

(Taylor, 1955) at work in our everyday accounting practices,

has led us both to locate the sources for all our social activities

as cognitions inside the heads of individuals (iii) and to characterize these sources in

terms of rules, or laws, i.e., in terms of regularities and repetitions

within single, systematic orders of connectedness!!! It

has led us also, to ignore precisely those events which occur

not only between people and which occur only once

without repetition, but the importance also of all those complex

events involving the chiasmic intertwining of influences

from different multiple sources (Merleau-Ponty, 1968).

Why is such chiasmic intertwining

of such importance? Both Merleau-Ponty (1962, 1968) (iv)

and Bateson (1979) take binocular vision as a paradigm. Bateson,

in his discussion of the question of "What bonus or increment

of knowing follows from combining information from two

or more sources?," notes that it takes the unmerged combining

(v)

of "at least two somethings to create a difference"

(p.78 ). In particular, something special happens, he notes,

in the optic chiasma (the crossing of the optic nerves from the

two eyes in the hypothalamus of the brain): "the difference

between the information provided by the one retina and that provided

by the other" works to help the seer add "an extra

dimension to seeing" (p.79), the dimension of depth.

Instead of seeing things as just large or small, we see them

as near or far.

But in considering seeing with

two eyes, are we, perhaps, getting just a little ahead of ourselves,

and moving to a higher level of complexity before considering

seeing "something" with just one eye? Perhaps we should

consider, first, what is involved, even with one eye, in scanning

over a face and seeing it - with all its changing expressions

- as the same face, only now as a smiling face, now as

frowning, now as sad, as welcoming, as threatening, and so on?

How do we join together all the different fragments collected

at different moments into a coherent, unitary whole, into the

"seeing" of a person's face? That seeing a person's

face as a face - evaluating it as a face - is an

achievement in which it is possible to fail, is shown by Sacks's

(1985) Dr. P. Although he knew perfectly well what eyes, noses,

chins, etc., were, he could not spontaneously recognize people's

faces as such, and thus it was that he mistook his wife's face

for his hat.

Thus, to understand what is possible

for us within such dialogically-structured events, and only within

such events, we must think of such relations in some radically

new ways. Indeed, as we shall see, we must think of them in extra

ordinary terms, in terms that can perhaps shock us into spontaneously

responding to the events occurring around us in uniquely new,

first-time ways.

What is at work here, as I see

it, is the kind of understanding that Wittgenstein's (1953) characterized

as that which "consists in 'seeing connections'" (no.122).

It is a kind of understanding that we might call a "relationally-responsive"

form of understanding, to contrast it with the "representational-referential"

forms of understandings more familiar to us in our intellectual

dealings with our surroundings.

But these relationally-responsive

forms of understanding all entail our seeing connections and

relations within a living whole, a whole constructed or

created from many different fragmentary parts, all picked up

in the course of one's continuous, living, responsive contact

with a particular circumstance in question, whether it is a text,

a person, a landscape, or whatever. So, perhaps we were not so

ahead of ourselves in seeing the kind of chiasmatic interweaving

that occurs in binocular vision, as paradigmatic of the creation

of many further "relational dimensions" in other spheres

of understanding. For, as Merleau-Ponty (1968) points out, this

kind of chiasmatic interweaving seems to be involved in all our

bodily understandings of our relations to our surroundings. "There

is a double and a crossed situating of the visible in the tangible

and of the tangible in the visible; the two maps are complete,

and yet they do not merge into one" (p.134). Indeed, "my

two hands touch the same things because they are the hands of

one same body... [and] because there exists a very peculiar relation

from one to the other, across corporeal space - like that holding

between my two eyes - making my hands one sole organ of experience"

(p.141).

These understandings - the creation

of these relational dimensions - might range all the way from

simply "seeing" a person's facial expression as a smile

or their utterance as a question, to 'seeing' quite complex connections

between people's behaviors in their lives - as, for instance,

Margaret Schegel in E.M. Forster's Howard's End 'saw'

connections between her forgiveness of Herbert Wilcox's sexual

peccadillos and his lack of forgiveness of those of her sister.

But all such understandings have their beginnings in those moments

when something occurs which "moves" or "strikes"

us, when an event makes a noticeable difference to us because

it matters to us. "There is, it seems to us," remarks

T.S. Eliot (1944), "at best, only a limited value/ in the

knowledge derived from experience. The knowledge imposes a pattern,

and falsifies,/ for the pattern is new in every moment/ and every

moment is a new and shocking/ valuation of all we have been"

(p.23).

In other words, for something

to make a difference that matters to us, something must surprise

us, be unanticipated, unexpected, fill us with wonder. But, as

Fisher (1998) notes:

The experiential world within

which wonder takes place cannot be made of unordered, singular

patches of experience. We wonder at that which is a momentary

surprise within a pattern that we feel confident we know.

It is extra ordinary, the unexpected. For there to be

anything that can be called "unexpected" there must

first be the expected. In other words, years or even centuries

of intellectual work must already have taken place in a certain

direction before there can be a reality that is viewed as ordinary

and expected" (p. 57, my emphasis).

In other words, taking into account

both Eliot's and Fisher's comments, wonder occurs when something

which we took to be not only complete but also finished in its

growth or development, suddenly exhibits a yet further inner

articulation. And it is when such an unexpected change as this

occurs against the background of our orderly, everyday, shared

understandings and accounting practices, that such events can

'strike us with wonder', can 'move' us, and can make a difference

to us 'that makes a difference'. These are the moments when,

as George Steiner (1989) puts it, "the 'otherness' [of the

other]... enters us and makes us other" (p.188). It is our

passion for wonder - a gift made available to us by our shared,

chiasmically or dialogically-structured, accounting practices,

by our shared expectation that the future will be an orderly

continuation of the past - that distinguishes us from all other

living animals.

The emphases here, then, on the

importance of our body's expressive responsiveness to events

occurring in our surroundings that make a difference to us, and

the dialogically or chiasmically-structured nature of such momentary

'moving' events, suggests the following set of questions about

the nature of learning:

- To what extent does our learning

depend on our bodily involvement in (and vulnerability to) events

that can provoke surprise and wonder, as well as anxiety and

risk, in us?

- To what extent is it important

that those teaching us have that kind of continuous 'in touchness'

with us, so that at various crucial points in their teaching,

they are able to say to us: "Attend not to 'THAT' but to

'THIS';" "Do it 'THIS WAY' not 'THAT WAY'"?

- To what extent is our living

involvement in a whole situation necessary for us to get an evaluative

grasp of the meaning for action of a small part of it - as when

a music teacher points out a subtle matter of timing, or a painter

a subtle change of hew, or a philosopher a subtle conceptual

distinction, such as that between, say, a mistake and

an accident?

- Is learning possible without

the bodily risk of, at least, disorientation and confusion, and

without the surety of being able "to go on"

(Wittgenstein), as guides to inform us as to the value

of our relations to our surroundings?

- And finally, is the individual

pursuit of truth possible, without being immersed in an ongoing,

unending, chiasmically-structured dialogue with the others and

othernesses about us - given that we all must continually re-evaluate

our values as the world around us changes and develops, and the

order of multiple values we once thought adequate begin to reveal

themselves as inadequate?

Notes:

(i)

In using the term chiasmic, I am following the lead of

Merleau-Ponty (1968) who entitles chapter 4 - in his book The

Visible and the Invisible - "The Intertwining - The

Chiasm." I cannot pretend to say what "chiasmic or

intertwined relations" in fact are. But what is clear, is

that here is a sphere of living relations of a kind utterly different

from any so far familiar to us (such as causal or logical relations)

and taken by us as basic in our intellectual inquiries. All I

can do here, is to begin their exploration.

(ii)

As is well known, early work by Mills (1940), followed by Scott

and Lyman (1968), directed attention toward the importance of

all members of a speech community being trained into an extensive

network of normative "background expectations." It

is these anticipations that work to hold all the different actions

within that community together as an intelligible whole. Members

failing to satisfy such background expectations in their actions,

will puzzle, bewilder, or disorient other members who will then

question their conduct. An account is a linguistic device that

prevents "conflicts from arising by verbally bridging the

gap between action and expectation" (Scott & Lyman,

1968, p. 46).

(iii)

Descartes (1986) discounted the spontaneously expressed 'intelligence'

of our bodies entirely. As a result of his meditations, he claimed,

that "I now know that even bodies are not strictly perceived

by the senses or by the faculty of imagination but by the intellect

alone, and that this perception derives not from their being

touched or seen but from their being understood" (p.22).

(iv)

Typical comments by Merleau-Ponty are as follows: "The unity

of vision in binocular vision is not, therefore, the result of

some third person process which eventually produces a single

image through the fusion of two monocular images... it is not

of the same order as they, but is incomparably more substantial...

We pass from double vision to the single object, not through

an inspection of the mind, but when the two eyes cease to function

each one its own account and are used as a single organ by one

single gaze. It is not the epistemological subject who brings

about the synthesis, but the body..." (1962, p.232). And

elsewhere: "The binocular perception is not made up of two

monocular perceptions surmounted; it is of another order. The

monocular images are not in the same sense that the things

perceived with both eyes is... they are pre-things and it is

the thing" (1968, p.7).

(v)

I.e., not an averaging, or mixing, or fusing, or blending, but

something emerges out of the relations occurring within their

unmerged intertwining that is a new and unique living form with,

so to speak, a 'life of its own', and furthermore, a life shaped

by all the influences that went into its creation.

References:

Bakhtin, M.M. (1986). Speech

genres and other late essays. Trans. by Vern W. McGee. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind in

nature: A necessary unity. London: E.P. Dutton.

Descartes, R. (1986). Meditations

on First Philosophy: with Selections from Objections and Replies.

Translated by J.Cottingham, with an introduction by B. Williams.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Eliot, T.S. (1944). Four quartets.

London: Faber and Faber.

Fisher, P. (1998). Wonder,

the rainbow, and the aesthetics of rare experiences. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies

in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology

of Perception (trans. C. Smith). London: Routledge and Kegan

Paul.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The

visible and the invisible. Evanston, Il: Northwestern University

Press.

Mills, C.W. (1940). Situated

actions and vocabularies of motive. American Sociological

Review, 5, 439-452.

Sacks, O. (1986). The man

who mistook his wife for a hat. London: Duckworth.

Scott, M.D., & Lyman, S.

(1968). Accounts. American Sociological Review, 33,

46-62.

Shotter, J. (1980). Action, joint

action, and intentionality. M. Brenner (Ed.) The structure

of action, (pp. 28-65). Oxford: Blackwell.

Shotter, J. (in press). "Real

presences:" Meaning as living movement in a participatory

world. Theory & Psychology.

Shotter, J. (1993). Cultural

politics of everyday life: Social constructionism, rhetoric,

and knowing of the third kind. Milton Keynes: Open University

Press.

Steiner, G. (1989). Real presences.

Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, C. (1991). The dialogical

self. In Hiley, D.R., Bohman J.F. and Shusterman, R. (Eds.) The

interpretative turn. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp.304-314.

Taylor, C. (1995). Philosophical

arguments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1986). Thought

and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical

investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Back to list of contributors

Learning as systematic

modification of shared experience

- Vera John-Steiner

- Presidential Professor

of Linguistics and Education

University of New Mexico

At the most basic level, learning

is the ability of humans to improve the conditions of our existence.

This shared and distributed process implies both profound cognitive

interdependence and individual capacities for growth and change.

Starting with children's early dependence on their care-givers

to the collaborative activities of knowledge construction, learning

is a profoundly social activity. It takes place simultaneously

between and within individuals. Even in solo endeavors like preparing

this short paper I am engaged in dialogues with the organizer,

the other contributors to the Book of Problems initiative, members

of my cultural-historical (Vygotskian) community, and the texts

and conversations that help me abandon traditional definitions

of learning. These definitions invariably focus on the individual's

acquisition of skills and information and on the individual brain/mind.

An alternative definition may be as follows: that learning is

a systematic modification of shared activities and practices

as a consequence of previous experience on the part of communities

and individuals. Or, put more broadly, human learning is a necessary

aspect of human survival in coping with powerful natural, social,

economic, political and technological challenges.

In our work in Native communities

in the Southwest as well as with creative collaborators in the

arts and sciences we have identified different types of learning.

A. Observational Learning.

Among the Hopi people planting corn is a difficult task of placing

seeds carefully to be protected in an arid climate with little

water. Young children observe their elders in this activity as

well as in pottery and jewelry making. This form of observational

learning is also common in apprenticeship situations as well

as in scientific laboratories. Novices are part of the broader

social practices of their communities and their growing knowledge

becomes a resource for the group. (Lave, J. and Wenger, E. 1991).

B. Innovative/Exploratory

Learning.

When confronted with unexpected challenges such as hurricanes,

wildfires, 9/11 or AIDS human beings engage in new forms of problem

solving. They draw upon the vast traditions of innovation where

most inventors are anonymous. Exploration and a search for solutions

start at a very young age. (See Gopnik et al, 1999) Data gathering

and hypothesis testing is most fully documented in scientific

work but it is a mode of learning that cuts across community,

educational and family environments.

C. Institutional Teaching/Learning.

As Jan Visser wrote, most people see learning as "limited

to what happens in a purposefully structured learning environment

in which desired attitudinal or competence goals are to be achieved

along the lines of well designed processes" (2002). The

large majority of studies on learning focus on this restricted

range of activities where the teaching process is primarily verbal

or where children's activities are narrowly focused. In attempting

to broaden our sense of learning we need to go beyond the confines

of traditional classroom environments.

These three modes of learning

form a dynamic functional system within a set of problems or

within a particular context. The most important tests of learning

are not those administered to frightened children but to whole

societies whose ability to build on the consequences of their

past experience will lead to innovative change. And, while individual

learning is part of the process it is not limited to it. In summary,

learning is not restricted to an individual trait but is a social

activity. It is in building upon each others knowledge through

dialogue, collaboration, and the effective use of humanly crafted

artifacts that we develop resilient communities that can address

the increasingly complex challenges of our times.

Based on the above considerations

the question thus becomes: How would our understanding of learning

be transformed if its purpose were joint discovery and shared

knowledge rather than competition and achievement?

References

Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A. N. &

Kuhl, P. K. (1999). The scientist in the crib: Minds, brains,

and how children learn. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company,

Inc.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991).

Situated learning: Legitimate periperal participation.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Visser, J. (2002). The book

of problems (or what we don't know about learning). Proposal

for a Workshop with Interactive Discussion Session for the International

Conference of the Association for Educational Communications

and Technology, Dallas, TX, November 12-16, 2002 [Online]. Available

http://www.learndev.org/BOP-AECT2002.html.

- Back to list of contributors

The acquisition

of values and dispositions: Are there lessons to be learned from

socialization and acculturation?

- Gavriel Salomon

University of Haifa, Israel

-

The truth is that we have quite

a bit of expertise in the field of learning. But our expertise

is limited to mainly scholarly learning, particularly the acquisition

of facts, concepts, formulae and organized bodies of knowledge.

This kind of expertise we have is badly limited in three respects:

(a) We know how information is acquired but know far less about

how it is being transformed by the solo learner and by a team

of learners into meaningful knowledge. Only recently have we

come to realize that information is not knowledge and that the

acquisition of the former is hardly a necessary and surely not

a sufficient condition for the latter. (b) We know even less

about ways of turning knowledge into usable, rather than inert

knowledge. (c) Most importantly, though, is the fact that we

know how intellectual stuff is learned, but we know far less

about acquiring human values and learning to live by them. There

is expertise out there about the acquisition of values through

authoritarian indoctrination, on the one hand, and on the effects

of life-long socialization, on the other. However, the former

counters our own democratic values while the latter is not in

the hands of educators. So, no wonder that the domain of value

education is not one in which we have enough expertise.

More specifically, I am concerned

about two learning (inter)related issues of which we know very

little. The first follows directly from the last point made above:

What does it mean to acquire a stable, positive value disposition

toward peace and peaceful ways of resolving painful conflicts?

What does it mean to acknowledge the "contribution"

of one's own party to the conflict in which it is involved? What

does it mean in terms of one's sense of collectively-rooted identity?

What does it mean in terms of adherence to one's own collective

narrative? We seem to have some fair and empirically grounded

approaches to attitude change. But is this all that constitutes

the kind of value disposition alluded to here?

Related is the question of acquiring